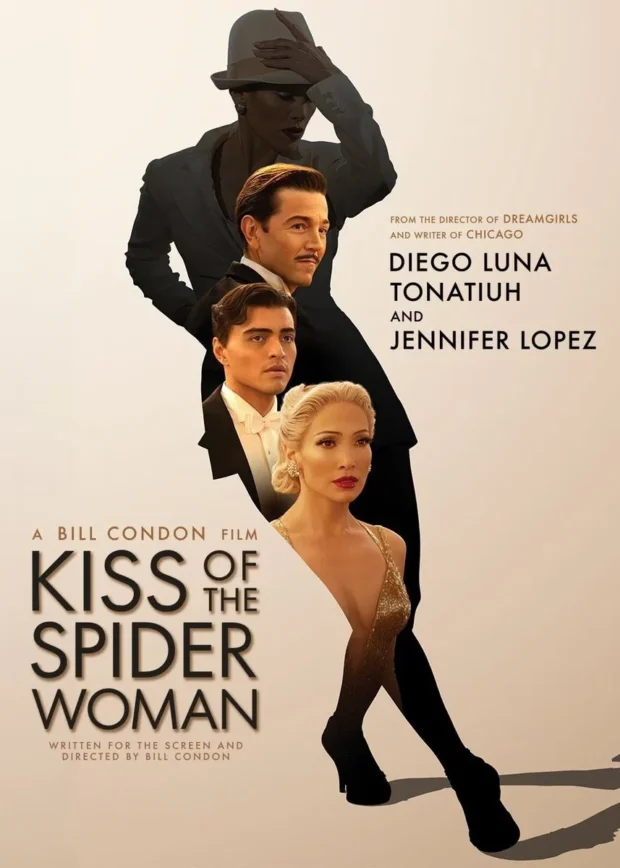

There’s a strange kind of beauty to a film that remembers what the old Hollywood musical used to be — and still dares to crawl through the mud of political despair. Bill Condon’s Kiss of the Spider Woman manages that balancing act with precision and heart, even when its edges fray.

Based on Manuel Puig’s 1976 novel — already a film, a play, and a Tony-winning musical — this new adaptation brings the material full circle. Condon, who knows the anatomy of stage-to-screen transformations better than most (Dreamgirls, Gods and Monsters), builds a world that’s at once claustrophobic and feverishly glamorous.

Set in 1981 during Argentina’s Dirty War, the film finds political prisoner Valentin (Diego Luna) sharing a cell with Molina (Tonatiuh), a trans woman jailed for “corrupting a minor.” Their lives could not be more different, yet the grim intimacy of the cell forces a slow, painful connection. Unbeknownst to Valentin, Molina is being coerced to spy on him — a secret that grows heavier as love seeps through the cracks of manipulation.

Condon splits the film between the cold, hard gray of prison reality and the Technicolor glow of Molina’s imagination. When the lights dim, Molina escapes into cinematic fantasies starring Jennifer Lopez as Ingrid Luna — a screen siren of impossible grace and danger. These sequences are shot like classic MGM dreamscapes: sweeping gowns, velvet lighting, and choreography that feels half-dream, half-desperation.

Lopez, at this stage of her career, knows exactly what she’s doing. She’s not just channeling old Hollywood glamour — she’s dissecting it. There’s a meta layer to her performance, as though Lopez, ever the modern diva, is consciously playing an echo of the star system that made her. You see shades of Rita Hayworth, yes, but also the cool self-awareness of an artist who’s survived the same machine.

Diego Luna brings both steel and sympathy to Valentin. He’s a revolutionary haunted by pragmatism — the kind of man who would weaponize someone’s affection if it meant saving others. Tonatiuh, meanwhile, delivers the film’s heart. Their Molina is complex, witty, and quietly heroic, resisting the film’s temptation to paint her as a martyr.

The cinematography by Tobias A. Schliessler (Beauty and the Beast) captures both worlds with deliberate contrast: the prison sequences are drained of warmth, filmed in harsh whites and iron blues, while the fantasies explode in saturated color. It’s not subtle, but it works — especially when the camera lingers on Lopez’s Ingrid mid-performance, her sequins catching light like a blade.

Musically, Condon keeps the songs contained within Molina’s imagined world — a smart move. The tunes by John Kander (with posthumous lyrics by Fred Ebb) retain that unmistakable Broadway melancholy. “Where You Are” stands out, equal parts seductive and sorrowful, echoing the theme of survival through artifice.

Still, Kiss of the Spider Woman isn’t without flaws. Condon’s pacing sags in the second act, and the prison-set dialogue scenes feel too stagey. You can sense his reverence for the material, but also his hesitation to fully reimagine it. The political backdrop remains gestural rather than visceral — as though Condon feared drowning his musical in too much darkness.

Yet, when the film commits to its contrasts — when Molina and Valentin blur into the fiction of Luna’s world — it achieves something rare. It becomes a film about cinema itself: how we use stories to survive what reality refuses to soften.

Roadside Attractions will release Kiss of the Spider Woman in select theaters on October 10, 2025, after its quiet debut at Sundance earlier this year. Don’t expect a massive marketing push — this is one of those films that will find its audience slowly, by word of mouth, not billboards.

Why Kiss of the Spider Woman Still Matters

Old Stories, New Flesh

Condon’s adaptation shows that a classic text can evolve — not just through gender or politics, but through form and music.

Jennifer Lopez as the Eternal Star

Her Ingrid Luna is both performance and confession — a layered reflection of Lopez’s own stardom.

Fantasy as Survival

Molina’s imagined musicals aren’t escapism — they’re resistance. In fantasy, she finds dignity.

Style with Substance

The sharp contrast between prison grit and cinematic glamour isn’t decoration; it’s the film’s central metaphor.

A Fragile but Earnest Revival

It’s imperfect, but the sincerity of its performances keeps the film from collapsing under its own nostalgia.