A New Wind Blows Through Period Cinema

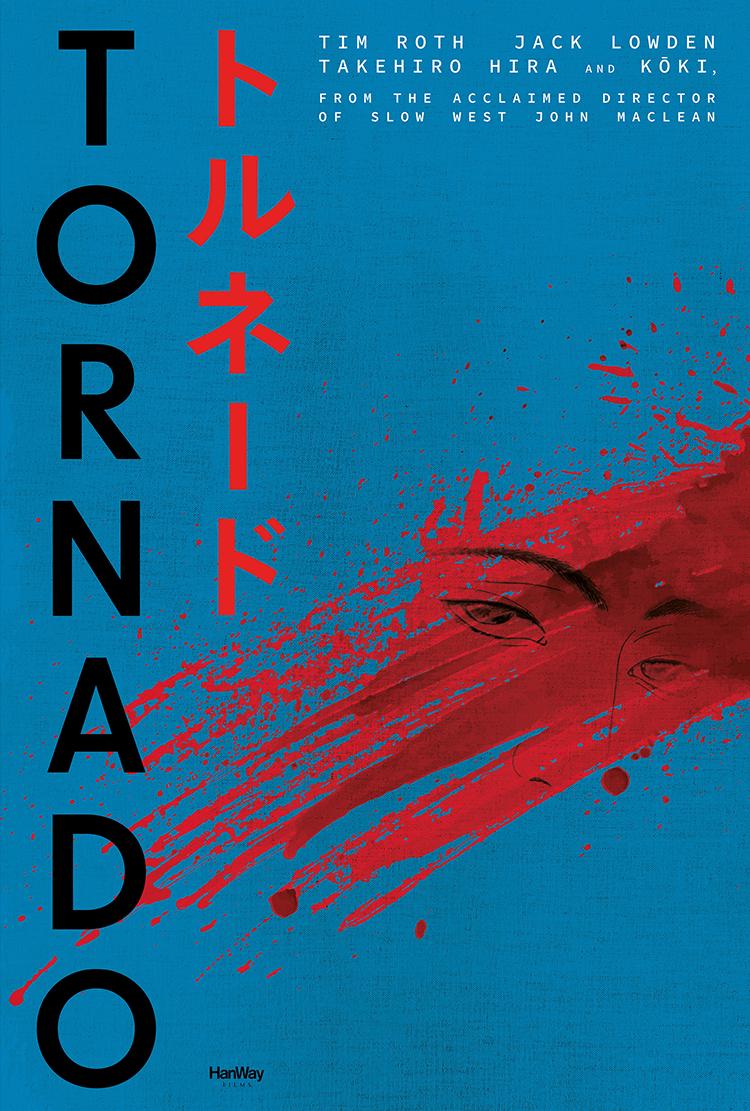

John Maclean's “Tornado” immediately catches the eye as more than just another costume drama. Set in 1790s Britain, the film appears to be crafting something far more intriguing than the usual genteel period fare – a gritty survival thriller that pits a young performer from a traveling puppet show against Tim Roth's criminal gang leader, memorably named Sugarman. The casting of Kōki, primarily known as a model and songwriter, in the title role suggests a fresh perspective on British historical narratives.

The film's premise – involving stolen gold, puppet shows, and what promises to be a violent chase across 18th-century Britain – reads like a magnificent hybrid of “Barry Lyndon” and “Hard to Be a God,” with perhaps a dash of Takashi Miike's wild energy. Lionsgate UK's commitment to a May theatrical release suggests confidence in its commercial prospects beyond the festival circuit.

Local Heroes and Global Stories

The festival's choice to bookend itself with “Tornado” and “Make It To Munich” creates a compelling narrative arc. While the opening film reaches for international appeal with its star power and genre-bending approach, the closing documentary grounds the festival in deeply Scottish soil. Martyn Robertson's “Make It To Munich” follows a story that could only emerge from Scotland's twin passions: football and medical innovation.

The documentary's subject matter – a young footballer's journey from near-death to cycling to Euro 2024 – carries echoes of earlier sports documentaries like “Senna” or “When We Were Kings,” where the sporting element serves as a gateway to deeper human truths. The involvement of Professor Gordon Mackay adds a layer of scientific achievement to what might otherwise have been a straightforward tale of persistence.

A Festival in Transition

This 21st edition marks a significant transition, as CEO and Festival Director Allison Gardner takes her final bow after three decades of service. The program she's assembled feels like both a celebration of the festival's history and a bold statement about its future. The inclusion of high-profile UK premieres like “The Return,” reuniting Ralph Fiennes and Juliette Binoche, sits comfortably alongside more experimental fare and local productions.

The decision to feature James McAvoy in conversation represents more than just star power – it's a recognition of Glasgow's role in nurturing world-class talent. McAvoy's presence bridges the gap between the festival's local roots and its international aspirations.

Looking Forward

As streaming platforms continue to reshape the film landscape, festivals like Glasgow play an increasingly vital role in celebrating the communal experience of cinema. The mix of world premieres, established stars, and emerging talents suggests a festival that understands its dual responsibility to both entertain and challenge its audience.

The inclusion of Amazon Studios' “Fear” among the world premieres indicates that streaming services now view festivals like Glasgow as valuable launch pads for their content. This evolution might prove crucial for the festival's future relevance in an increasingly digital age.

Critical Perspective

What makes this year's lineup particularly intriguing is its refusal to be easily categorized. The opening film alone subverts multiple genres – period drama, thriller, cross-cultural narrative – while the closing documentary transforms a sports story into a meditation on human resilience and medical innovation.

This program suggests a festival comfortable with its identity yet unafraid to evolve. In an era where many festivals struggle to balance artistic merit with commercial viability, Glasgow appears to have found an intriguing middle ground.

The question remains: Will “Tornado” prove to be more than the sum of its intriguing parts? Can it transcend its genre-blending premise to deliver something truly memorable? The world premiere at Glasgow will tell, but the elements – from Tim Roth's reliable intensity to the bold casting of Kōki – suggest something worth watching closely.

What potential do you see in this growing trend of international actors taking leading roles in British period pieces? Does it signal a broader shift in how we approach historical narratives in cinema?