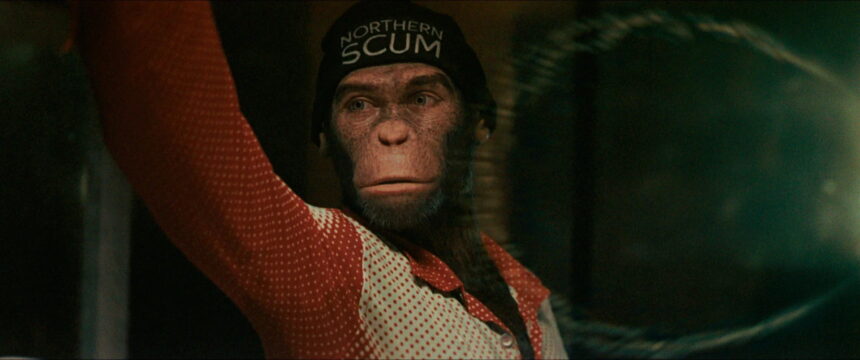

When I first heard about “Better Man,” I'll admit I was equal parts intrigued and baffled. The notion of portraying British pop icon Robbie Williams – a larger-than-life personality known as much for his swagger as his songs – as a computer-generated monkey seemed like the kind of fever dream that could only emerge from a particularly adventurous studio pitch meeting. Yet here we are, watching this $110 million experiment crash spectacularly at the box office with numbers that would make even the most optimistic executive wince.

The film's dismal $1 million opening from nearly 1,300 theaters in the U.S. tells only part of the story. Even more telling is its lukewarm reception in Williams' home territory – the UK market where he remains a beloved figure – managing just $4.7 million to date. These numbers suggest a fundamental disconnect between creative ambition and audience appeal that goes beyond mere marketing challenges.

What makes this particular failure so fascinating is its budget. At $110 million, “Better Man” cost more than recent musical biopics like “Elvis” ($85M) and “Bohemian Rhapsody” ($52M) – films centered on artists with far broader international appeal. Paramount's decision to acquire the film for $25 million now looks like catching a falling knife, albeit a surprisingly expensive one.

The CGI monkey conceit, while creatively bold, emerges as both the film's most distinctive feature and its biggest liability. In an era where audiences have grown increasingly sophisticated about visual effects, the decision to filter Williams' larger-than-life personality through a digital primate avatar seems to have created an emotional distance that even positive reviews couldn't bridge.

Personal Impression: What fascinates me most about “Better Man” is how it epitomizes the current tension in Hollywood between creative risk-taking and commercial viability. While I admire the audacious artistic choice to portray Williams as a CGI monkey, it's a decision that seems to have forgotten the fundamental appeal of musical biopics: the human connection. The film's failure might serve as a cautionary tale about the limits of technical innovation when it comes at the expense of emotional authenticity.

What does the failure of “Better Man” tell us about audience preferences in musical biopics? Are viewers more interested in authentic human performances than technical innovation?